How to: NDA during “Patent Pending”

You may have heard chats in entrepreneurial coffee hangout places about using a patent to protect your invention.

You wonder if you should do the same for your own invention.

Are patents truly effective and how do they work?

Contents

The first American patent was granted to Samuel Hopkins in 1790 by President George Washington for a fertilizer manufacturing product.

![]()

Since then, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) now recognizes more than six million patents. In 2015 alone, the number of patent applications in the US was over 600,000.

Although obtaining a patent is generally a slow and expensive process, it gives you a monopoly on the ownership, use, sale and licensing of that invention for a certain number of years (20 years for a non-design patent in the US and 17 years for a design patent).

This means that during this time, no one else can steal, use or reproduce your invention without your permission and if they do, you will have legally enforceable rights against them including injunctions and a claim for damages.

The best type of patent protection that you can get in the US is through a successful nonprovisional patent application.

If you apply for a nonprovisional patent with the USPTO, it currently takes an average of 2 to 3 years for the patent to be issued.

The USPTO provides a patent dashboard that displays the average waiting period and backlogs for the patent process.

So not only does it take a while before you can acquire proper patent protection, but it’s also expensive.

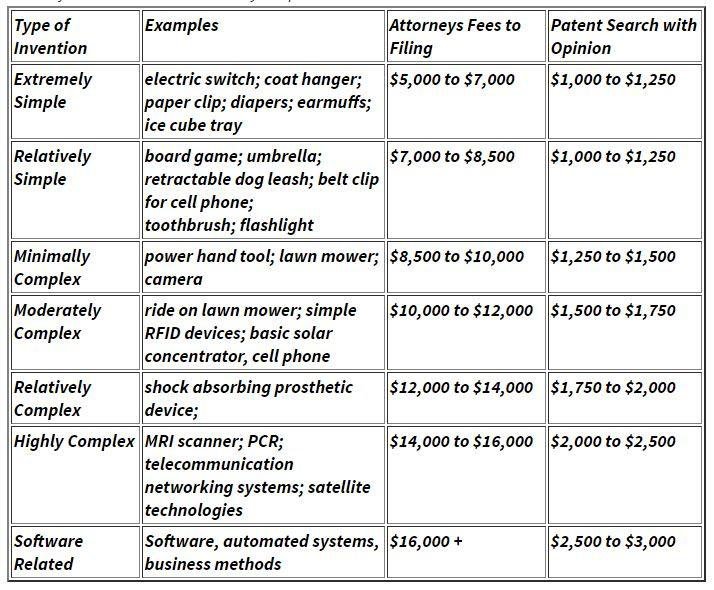

Here’s a chart produced by the website IPWatchdog.com that shows you an estimate of how much it costs in term of attorney’s fees alone for a patent application:

Patent filing fees will be on top of this and can range considerably. Here’s a snapshot from the USPTO:

Provisional patents aka “Patent Pending”

A provisional patent application is an alternative way to a nonprovisional patent application which costs less money and is more flexible.

You’ll be able to use the title of “patent pending” on your invention once your provisional patent application is issued.

However, beware that the provisional patent application doesn’t actually give you any legally enforceable rights against a party that copies your invention. It merely establishes an early filing date for you and puts others on notice that you have an intention to patent your invention.

A provisional patent application can only buy you an extra year.

If you want to retain any possibility of full patent protection, you must file a nonprovisional patent application within a year of filing your provisional patent application.

Nevertheless, there are many benefits of a provisional patent application including:

- You obtain an official “patent pending” status that you can use to label your invention.

- If you follow through the provisional patent application to a nonprovisional application, you will have the benefit of an early filing date (that is, the date that you filed the provisional patent application).

- You will be able to continue to work on improving your invention for a year before you have to apply for a nonprovisional patent.

- You can use the “patent pending” status to attract potential investors.

- You can issue certified letters to businesses who are uninformed or wrongly using your invention to inform them of your “patent pending” status and your intention to take legal action against them after your nonprovisional patent is issued.

- A declaration of “patent pending” status also tends to discourage potential copycats from targeting your invention, especially if a lot of investment is required to do the copying, as there’s the possibility that they could lose all rights to reproduce the invention once your nonprovisional patent is issued and be sued by you later.

-

Once you file a nonprovisional patent application, you can no longer make any modifications or improvements to your invention.

A provisional patent application on the other hand, allows you to apply for a second (or third etc) nonprovisional patent if you make modifications and improvements to your invention.

-

Nonprovisional patent attorney and filing fees cost a lot more than a provisional patent one.

If you find out that there’s no real market for your invention, you can abandon the patent process and you lose less money with a provisional patent application.

Gaps in the “Patent Pending” status

However, despite the benefits, there are some gaps in intellectual property protection when it comes to being in the “patent pending” status.

For one, you don’t have any legally enforceable rights against any unauthorized copying, use or publication of your invention while in “patent pending” status.

Because of this, there are still risks if you share details of your invention with third parties such as manufacturers, potential licensees or distributors.

Another gap you need to be aware of is if you make modifications to your invention.

All modifications need to be accompanied by a new provisional patent application if it wasn’t detailed in any of the previous ones. If you don’t, those modifications will not be covered by patent protection later when you move into the nonprovisional patent application stage.

There’s also the possibility that your application for a nonprovisional patent may be rejected by the USPTO. If so, you will be left with no patent protection at all.

Enter the Non-Disclosure Agreement (NDA)

Because of these gaps, a non-disclosure agreement (NDA) will come in handy.

The NDA is a contract that requires another party that receives any confidential information (“Receiving Party”) from you (“Disclosing Party”) to keep your confidential information secret and also not to misuse the information without your permission.

There are generally 2 main situations that you should consider getting the NDA drafted and signed before you disclose confidential information in regards to an invention:

- A standard NDA for sharing your confidential information or invention with another party such as manufacturer or a potential licensee

- Or when you are looking to hire an independent contractor such as a developer to help you create a design or prototype

There are a few key terms that you should have in your NDA agreement:

-

Purpose of NDA.

Although not strictly necessary, by providing a purpose for the creation of the NDA and the reason for the sharing of confidential information, you establish a general direction and guideline for the agreement.

Here’s an example from FreePatentForms.com:

This second example is from IPWatchdog.com:

-

Definition of what is “confidential information”.

Confidentiality can extend to anything that you deem as confidential or proprietary including documents, designs, sketches, analyses, source codes, marketing plans, manufacturing processes and technical procedures.

But don’t go overboard and label all information disclosed as confidential, even if it isn’t.

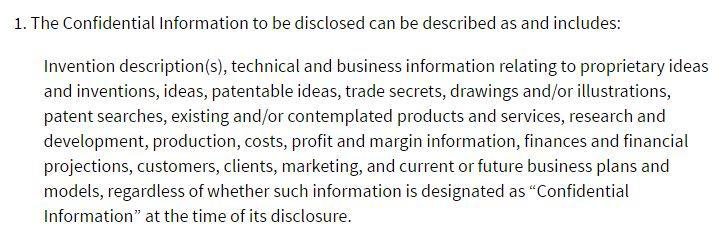

Here are 2 examples from IPWatchdog.com on definitions of confidential information when you have an invention or potential idea that you wish to patent.

Example 1:

Example 2:

-

Exceptions to what is “confidential information”.

You want to make sure that in general, the scope of your NDA is reasonable. Some courts will strike down an agreement that comes across as unreasonable.

For example, the Virginia court in Lasership, Inc. v. Watson, held that the NDA was unenforceable because the requirement of confidentiality applied too broadly and the terms of the NDA were to also apply indefinitely.

An important element to include in your agreement are the exceptions to confidentiality.

Once your provisional patent application is published, you won’t need confidentiality for information related to your invention any longer because the information would have entered the public domain. Because of this, it’s vital that you include this as an exception in your confidentiality requirements.

Other reasonable exceptions include information that the Receiving Party already possessed previously or acquired independently themselves as well as information that was provided to them by a third party that does not owe a duty of confidentiality to you.

Here’s an example:

Here’s another example:

-

Non-Use and Permitted Uses.

To ensure that it’s clear that the Receiving Party is prohibited from misusing your confidential information, you should include a clause that expressly covers the permitted uses of the information.

Here’s an example from Thoughtbot’s Mutual Non-Disclosure Agreement:

Another example:

-

Non-competition.

A non-competition clause bars a Receiving Party from using any of your confidential information for their own benefit without your permission or to compete with you.

Learn the difference between a “non-compete” and “non-disclosure”

Here’s an example from Docracy.com:

-

No Grant of Rights.

Since you’re in the midst of patenting your invention, you want to be very clear that by sharing your confidential information with the Receiving Party you’re not granting them any rights or licenses to your invention, at least not without your consent.

Here’s an example of a clause:

And a second example:

-

Authority Clause.

If the Receiving Party is an entity, i.e. company, make sure that the NDA is signed by a person who is legally authorized to do so on behalf of the entity.

To make it clear that you want a person with authority to execute the document, you can insert a clause in your agreement that the parties affirm that the individuals signing the NDA have binding authority.

Here’s a simple clause from the Canadian Corporate Counsel Association’s “Mutual Confidentiality and Non-disclosure Agreement“:

-

Non-circumvention.

It won’t be surprising if you have thought about the possibility of getting your invention eventually manufactured in China, which is the largest manufacturer in the world at present.

If you’re going to be sharing your confidential information with a party in a country like China, where the rules are different from the US, then you should consider using the “Non-Disclosure, Non-Use, Non-Circumvention agreement (NNN)” which is a slight variation of the NDA.

A non-circumvention clause prevents a Receiving Party from going past you to your customers. This happens when unethical manufacturers use your confidential information to create their own products and then, sell them to your clients directly.

Here’s an example:

-

Governing Law and Jurisdiction.

The governing law is the law that will be applied to the NDA if it ends up in court. The jurisdiction refers to the court that will be chosen to determine the matter.

For example, you may have the governing law as California but the jurisdiction as the New York courts.

Different jurisdictions and laws can result in different outcomes so you should definitely seek legal advice on this matter.

Here’s an example of a clause that you can use, taken from a NDA by Harvard Business School:

There’s always a possibility that when you are seeking help from more established parties to help you commercialize your invention, such as a potential licensee, investor or distributor, they may refuse to sign your NDA.

This is especially if they work with a lot of other inventors or they are into inventing products and services themselves.

If they hold bigger bargaining chips than you because you need them more than they need you, you may not be able to convince them to sign your NDA. If such a situation occurs, you will have to decide whether you want to take the risk of proceeding to work with them without an NDA or whether you should continue searching for more cooperative partners.

Nov 27, 2017 | Non-disclosure Agreements | Patents

This article is not a substitute for professional legal advice. This article does not create an attorney-client relationship, nor is it a solicitation to offer legal advice.